This article by Matt Danford originally appeared in Modern Machine Shop magazine.

“It all changed when Pringles moved into town,” Jeff Cupples says as he pulls onto the highway and away from the group of metal buildings bearing his family name. Driving across West Tennessee from Cupples’ J&J Company’s headquarters in Jackson to a satellite facility in Dyersburg takes about an hour – enough time for introductions and some background, beginning with how opportunities to help make the machines that make the potato chips fueled greater ambitions for what was then a simple tool and die shop.

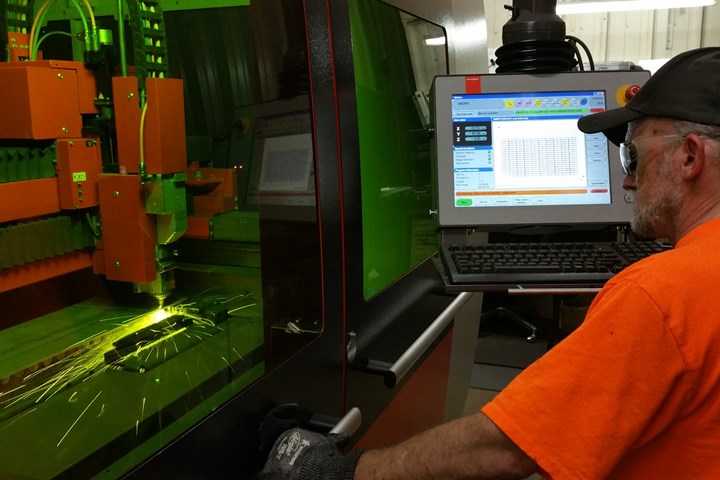

A walk through the 65,000-square-foot satellite plant reveals how far Cupples’ J&J has come. Equipment here ranges from mills, lathes and EDMs to press brakes, CNC rollers and robotic welders. All this, and we had yet to see a more expansive, more sophisticated mirror of the same capabilities at the nearly 40-acre, seven-building main campus, which also boasts a field service operation and some of the first Eagle and Bystronic fiber laser cutters of their kind on this side of the Atlantic. Suddenly, Jeff Cupples’ earlier use of the term “one-stop shop” no longer seems so cliché.

However, what truly sets this nearly 400-employee company apart cannot be found in the equipment itself, either in Dyersburg or in Jackson. The diversification and expansion of machining and fabricating capabilities have been driven in part by adhering to one central idea. As Cupples puts it, “Every part has its own identity” – that is, a way to shape the metal that, at a particular point in time with a particular set of resources and customer requirements, is more cost-effective than any other option.

Finding each part’s “identity” is a distinctive strength of Cupples’ business. How does a shop scale and diversify its capabilities without losing the full efficiency of each of those capabilities? How can capabilities as different as laser cutting and CNC milling be used effectively together within the same organization? For Cupples’ J&J, the answer begins with a job quoting system that recognizes and leverages the strengths of various manufacturing processes and equipment.

Finding a New Identity

Away from the din of the equipment at the satellite plant, the drive back to Jackson provides a welcome opportunity to talk big-picture turning points. We discuss the 1989 move from manual machining to CNC, and, prior to that, the 1981 addition of welding and forming equipment for machinery components. However, Cupples quickly zeroes in on the 1997 purchase of the company’s first laser cutter.

At that time, the primary interest was in supporting the CNC machining and fabricating equipment with a faster means of drilling holes and cutting simpler geometry. This newfound speed (and quality, in many cases) drove expansion by deepening relationships within the region’s lawn and garden industry as well as with large customers like MTD Products, Caterpillar, Kubota and Kellogg’s (which purchased Pringles from Procter & Gamble in 2012). The laser also made the company a go-to source of emergency orders to help keep customers’ machinery running. “The next thing we knew, we were running it 24 hours a day, six days a week,” Cupples says.

Laser cutting also opened new opportunities to pursue production-volume fabricating contracts. No longer just an enabler of the mills and lathes, this capability has since become a particular point of pride, to the point that the company has been known to repair, modify and even design laser cutting nozzles from scratch. It is a lynchpin in a strategy that depends on fabricating and machining capabilities to support one another, both through tooling for production-volume work and through complementary operations on the same parts. “We’ll laser-cut something, bend it, machine bosses and robotically weld it all together, then maybe machine after the fact,” Cupples says. “Is it laser and machining, or maybe machining then laser? What about waterjet? What is the best-cost scenario for the customer?”

By early 1998, just months after the first laser installation, Cupples was working on spreadsheet-based automation to help answer such questions more efficiently. Meanwhile, he says much of the competition was simply “plugging in numbers,” charging overly standardized rates with no basis in shopfloor reality.

Laser-Like Quoting Precision

Zipping through the Jackson facilities on a golfcart, we pass by sunglass-clad laser operators hurriedly scooping up freshly cut parts from sheet-metal nests. Moments later, we pause to take in specialty machining operations on a massive boring mill. Each of these jobs requires vastly different priorities and skillsets to succeed, but both began the same way: carefully timing cycles to map out potential process chains and determine which of four individual teams — production fabricating, specialty fabricating, and production and specialty machining — would be best suited to handle the work. “It’s like a bunch of smaller companies working together,” Cupples explains. “Whoever does the most work is the master of the project, and they subcontract out to the other divisions.”

To determine the “master” division for new work, Cupples uses the same Microsoft Excel-based system that the estimators in each division employ for “subcontracting” to one another. During this process, the idea that “every part has its own identity” manifests in the following ways:

Estimating trumps guesstimating. Cupples says many estimators are trained to “divide everything by .8” when accounting for the fact that no process is 100-percent efficient. However, part of every part having its own identity is assuming that every part also has its own efficiency. A realistic number for any given job might be derived from timing cycles as well as experience. For example, a particularly heavy part might drive the efficiency estimate for a press brake lower than machine timing cycles might suggest.

No averaging. Averaging rates for different workcenters into a single price can be efficient, but problems can arise when the mix of work changes, Cupples says. “Average your three-quarter-of-a-million dollar HMCs with everything else,” as he puts it, and shops will likely find that “all those big machining centers will be loaded” because they will likely be underpriced. Meanwhile, less valuable equipment likely will be overpriced, and thus more difficult to fill. At Cupples’ J&J, rates differ widely from workstation to workstation and from job to job.

Pricing is granular. In fact, the same machines often command different rates for different work. For example, factoring setup time for the job into every quote might lead the same workstation to command a lower rate for production-quantity parts than for lower-quantity, specialty parts (which generally require more setup). “We pay for (a machine) in the hours that we run it,” Cupples says. “Accountants will say the machine has value 24-7, but in our experience, you can’t charge a 24-7 rate for setup. You can really only charge for when it’s working.”

“Overhead” can be job-specific. Like setup or programming (which also factors individually into workcenter rates), costs associated with quality control and shipping can vary from job to job. Similarly to averaging workcenter rates, Cupples says he learned long ago that wrapping such costs into overhead can be a mistake. Even with a generalized “higher rate to cover the unknowns,” he says the result is often a situation in which “the job report says you’re making money, but your financials say otherwise.”

Pricing is fluid. Quality control costs and other variables are all pulled in as individual workcenter rates from a tool that is aptly named “the Matrix.” This companion spreadsheet outputs a literal matrix: a section of spreadsheet outlining as many as 16 possible chargeout rates for a given workcenter or cell per payback period, which is typically set to between 3 and 5 years. Estimators can enter different shift scenarios and setup hours for workcenters as they experiment with meeting quoting targets.

Automation is essential. With workcenter rates set, estimators have only to enter variables associated with the job – material data, part volumes and routings, labor hours and so forth – and the quote updates accordingly. “We can change work center rates as needed for new work that may have much higher or lower efficiency, or for new cells,” Cupples says. “We can actually load hours run on the machine or cell during the previous year, and it will tell us if our rate still creates profit and payback.”

Although the company’s meticulous estimating process would never work if all of these calculations were manual, it still requires significant time and effort. In fact, Cupples has considered upgrading to multiple enterprise resource planning (ERP) software packages over the years. However, most of the systems trialed so far have the same problem: “You have to lie to it,” he says. “Running multiple customers’ parts in a cell at the same time is difficult for ERP systems to capture.”

Reflecting Shop-Floor Reality

During the walking tour of the Dyersburg satellite plant, we paused to take in the “broken” production cell pictured below. This is one of many examples of a single employee running a machine with a relatively high-chargeout rate (the laser) alongside a machine with a relatively low-charge-out rate (the press brake). This cell is “broken” in that the machines generally run completely different parts, often for multiple customers. “This is how we compete with China,” Cupples says.

However, broken cells tend to break any shop management software that ties the labor allocated to different workcenters directly to payroll, Cupples says. With the spreadsheet, in contrast, it is easy to simply “combine those costs and make a workcell rate.” Alternatively, he might “let the high-dollar workcenter cover the labor” to get more from the lower-value machine.

Beyond the payroll issue, “broken cells” have also stymied systems that expect operators to scan work in via barcodes. “How do you clock into two different parts on the same machine?” Cupples asks, although he had already answered his own question. Whatever the scenario, “lying” to a shop management system (in this case, perhaps by getting creative with the scanning process or manually overriding labor input later) can be cumbersome.

As an example, Cupples cites a capability that he has yet to see replicated in other software: easily and quickly determining whether additional efficiencies gained from running overtime would be worth the additional labor costs. With his own system, there is no need to enter 47.5 hours for an employee that really worked 45 hours, but earned overtime for 5 of those hours (so, 40 hours regular pay, 5 hours overtime). This is because the system automatically changes the work center rates according to the overtime actually worked. Nor is there any need to create additional workcenters manually within the system – say, “OT1,” “OT2” and so forth – to account for overtime costs. Estimators simply change a single spreadsheet field, and the quote updates accordingly.

Cupples says such flexibility seemed far-off when he first developed a one-page spreadsheet to streamline and homogenize quoting across what were then brand-new business divisions. The company’s growth since then is testament to the success of its approach. At the time of this writing, that approach seemed unlikely to change anytime soon. “What we do takes less people and less time, and it’s more accurate,” Cupples says.