This article by Matt Danford originally appeared in Modern Machine Shop magazine.

Calling Ace Stamping & Machine Co.’s toolroom a toolroom does the operation a disservice. What happens here is production machining by any definition, and the transformation from toolroom to captive CNC machine shop has been both rapid and impactful.

Not that any of this is immediately obvious to most visitors. After all, the company’s main, 76,000-square-foot plant is filled not with knee mills and workbenches, but lines of punch presses and racks of sheet metal.

During a walkthrough, the repetitive “kerchunk” of slamming metal dies, the whir of hydraulics and the clank of parts dropping into bins make conversation difficult. Darin Sewell, senior toolmaker and general manager, seems happy to return to the relative quiet of the milling machines in his own work area, where talk proves easier. “Everything happens for a reason, and it’s our job to find out why,” he says about supporting the fabricating business. “If something’s happening on the first station (of a progressive die), is that affecting what’s happening on the last station? You’re looking at the whole system — you have to understand how everything works together and look at the mechanics of the situation to make a finished part.”

However, new opportunity has made the contrast between the toolmaking and fabricating areas less stark, he says. Now armed with four new CNC VMCs, Mr. Sewell and his team have been tasked with developing and maintaining a fast, repeatable process not unlike the ones running in the main facility. “Our work here used to be all about getting it done well,” he says. “Now, it’s about getting it done fast, too.”

When machine shops struggled with parts for commercial-grade Insinkerator systems or refused the work entirely, the threat of a ripple-effect disruption in the company’s own stamping production became all too real.

Despite the change in focus, spending time with Mr. Sewell makes clear that the company’s greatest asset in moving into production CNC machining was already in place. Without a fundamental toolroom education (in this case, developed over years of engineering and manufacturing jigs, fixtures and progressive die sets), Ace Stamping likely never would have obtained its first high-volume CNC contract, and the equipment investments likely never would have been possible.

He says as much, although not directly. “The customer had previously been going to dedicated CNC machine shops, but we looked at things differently,” he recalls. “We had an older machine at first, but our way (of machining the part) was faster and more consistent.”

Meanwhile, an HMC and two Swiss-type lathes have transformed operations at two co-located sister companies. Parts moving across these seven new machine tools, all of which were installed within 18 months, have provided what company Vice President James Haarsma calls “a robust increase” in annual revenue.

Terminating Risk

John W. Hamme had certainly had never seen a blockbuster about time-travelling killer robots when he coined the term “Insinkerator” in 1927, but he might not mind the natural association. A play on the word incinerator, Insinkerator is the name he chose for the company he founded to manufacture the product he invented: the garbage disposal. Located just a few miles away in Racine, Wisconsin, Insinkerator has purchased stamped garbage disposal components from Ace Stamping for decades.

However, grinding food waste as hard as solid bone requires more than just stamped components. In an Insinkerator system, food particles fall onto a spinning, plate-like shredder blade that throws them into the ridged inner walls of a surrounding grind ring. Mashed against the grind-ring teeth as the shredder blade relentlessly spins, food waste continuously flushes out of the unit and into the septic or sewage system. For durability, these two critical components (grind ring and shredder blade) are cast from high-nickel iron (NiHard). Despite Rockwell-scale hardness that Mr. Sewell says measures in the 50s, these castings must be finish-machined to ensure proper assembly and operation.

As a high-volume metal stamper, Ace Stamping had never concerned itself with such work. However, when machine shops struggled with parts for commercial-grade Insinkerator systems or refused the work entirely, the threat of a ripple-effect disruption in the company’s own stamping production became all too real. In response, the company turned threat to opportunity by letting Mr. Sewell try his hand at the parts. “We saw potential not only for direct revenue, but also to help support our own stamping lines by throwing ourselves into this work,” says James Haarsma, vice president at Ace Stamping. “Dedicating machines to the job sets us apart.”

However, justifying any investment required developing a solid process first. This task fell almost entirely to Mr. Sewell. In addition to a tough material, the variation inherent to working with raw castings made this a full-time job. Nonetheless, the reward proved to be well worth the temporary redeployment of one of the company’s few experienced toolmakers. Within three weeks, the shop was producing grind rings and shredder blades at production volumes, albeit in one size range. Now, the captive machine shop churns out approximately 200 parts per day in four different sizes.

Coming to Grips with Production

The parts’ geometry is not complex. Tolerances of ± .0025 inch for the most demanding features posed no problem for the shop’s workhorse machine at the time, a 2011-model VMC with an intuitive conversational programming interface. Generating the G code for the machining operations — OD and ID milling for the grind rings, and face-milling, drilling and reaming for the shredder blades — was a simple matter of importing the CAD files and following the CNC’s on-screen prompts.

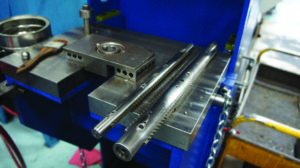

However, the corrosion resistance that makes NiHard useful for Insinkerator also makes the alloy tricky to cut. Machining at speed without losing too much time and money to broken cutters depended largely on Mr. Sewell’s capability to determine the right speeds, feeds and cutting depths. However, he ended up devoting most of his time to another fundamental concern. “Our first thought was, ‘How are we going to hold it?’” he recalls. “How are we going to hold it not just accurately, but repeatably? We can’t indicate (locate) each casting. We have to change over quickly.”

NiHard is “springy,” he explains, and with relatively thin walls, the grind ring castings are prone to distortion during machining. Additionally, dimensions can vary by as much as 1/16th of an inch or more from casting to casting. Distorting the part’s ID by clamping too forcefully or in the wrong place can make post-machining assembly impossible, assuming the casting still fits in the second, OD-milling station. Worse, the problem might not be immediately apparent. For example, a slightly smaller ID might be subjected to too much pressure from the OD milling station’s plug-like clamping device, a defect that might be discovered only after all milling was complete.

Although he lacked any CNC machining background, Mr. Sewell says years of experimenting and problem-solving in the toolroom served him well. Recalling the two weeks of process development, he says much of his time was spent “mounting indicators all over the machine” to study how the material reacted to test cuts and “going through tons of prototype fixtures that worked, but didn’t work well enough,” he says. Eventually, he developed a sequence for tightening strategically placed ID milling clamps to specific torque levels. “I’d go home at night and envision scenarios in my head — ‘I think we can make it better this way,’ or ‘let’s try that,’ — and eventually, we got there,” he says. “Once we had a good process, we made the hard tooling.”

That first grind ring casting had the thinnest walls of the entire part family, he adds. This made it ideal for developing the kind of repeatable, standardized setup process that, albeit with a few tweaks, would work for larger, more forgiving castings as well. “Everything we corrected along the way was a little step toward a perfect part,” he says. “Then, it became a matter of making it fast and repeatable.”

With a process solidified, management was ready to invest more than just time in its CNC machining capability and capacity. The first purchase was an Okuma Genos M560 VMC. This machine enabled an immediate, 30% increase in speeds and feeds using essentially the same G code and setup. Mr. Sewell attributes this gain to a rigid, double-column design. A chip-to-chip tool-change time of less than 5 seconds, compared to the older VMC’s 30 seconds, has also significantly improved productivity, as has the increase in rapid-traverse speed from 275 ipm to more than 1,500. Thanks to these and other advantages, cycle times were reduced by nearly half. The captive machine shop now has three more VMCs: another of the same model, and two Okuma MB-46V machines, all of which are dedicated to machining castings.

Tools Are Just That

However, the inherent imprecision of the casting process limits the extent to which the process can be systemized, Mr. Sewell says. As a result, a skilled hand and toolroom-style thinking have proven just as valuable for keeping production running smoothly as developing the process in the first place. “Every part is unique, and every new person has to get a feel for it,” Mr. Sewell says about setting up the VMCs. “Every size has its own little idiosyncrasies that our people need to know how to deal with.”

Returning to the grind ring milling fixture, he says it requires some degree of “feel” to bring each ID milling clamp down to the proper torque setting, even with specific torque targets and a specific clamp-tightening sequence. On the second, OD milling fixture station, the situation is similar. The locating plug doubles as a clamp. Locating and fixturing simultaneously without “clamping a twist” into the part, as Mr. Sewell puts it, requires some degree of instinct. “If we have to beat it in there, it’s getting to tight, but if it just drops in, it’s too big. They’ll know if it goes in the right way, that it’s perfectly sized. (This manual process) provides a way to rapidly locate it, clamp it, and ensure proper size without having to measure every fifth part on a CMM. We just know if it fits nice, we’re there.”

Ace Stamping continues to expand its machining horizons. At sister company Shakespeare Machine Stamping, a manufacturer of abrasive wheel components that Ace Stamping purchased in 1990, two new Tsugami 3025B-II Swiss-type lathes have been employed to repeat the same strategy: that is, bringing a critical part in house in order to support the company’s own fabricating operation while also providing direct revenue stream. Meanwhile, an Okuma MB-4000H HMC has helped rejuvenate another sister company, industrial vise manufacturer Heinrich Vise, by replacing an older machine that continually broke down.

All of these machines were purchased from Morris Midwest, which Mr. Sewell credits for its quality service, support and, particularly, knowledge. (In fact, he credits a Morris representative for identifying the opportunity for Swiss-types in the first place, noting that “I didn’t even know what a Swiss-type lathe was.”) However, even the most sophisticated machining equipment backed by the most well-resourced and attentive dealer goes only so far. More than just Ace Stamping’s most important and profitable contract, the NiHard casting application serves as a continual reminder of the value of a fundamental shop-floor education, and of the fact that machine tools are just that: tools.