This article by Emily Probst originally appeared in Modern Machine Shop magazine.

Everything at Tomenson Machine Works is intentional. Every choice — from the work it takes on, to the flow of raw material to finished product around its 100,000-square-foot U-shaped facility, to the specific makes and models of its machining centers — is aimed at standardization. By standardizing its entire production process, Tomenson has found a way to not only run efficiently and predictably, but also train new employees with ease.

The path to simplicity has been long and has required dedication. Getting to this degree of standardization took time and effort on the part of three generations of family members, starting with Thomas Roake, who founded the shop in 1977. Thomas ran the shop until 1993 with his son Scott Roake (hence the riff on “Tom and son” for the company name Tomenson). In 1997, the company moved to its current location in West Chicago, Illinois. Scott is now the company’s president, and the third generation has taken leadership roles, with 24-year-old brothers Alex Roake as operations manager and Zach Roake as post-production/quality manager. Through the years, the family members have zeroed-in on a process that enables the company to ship more than half a million precision hydraulic manifolds per year, along with at least 20,000 other parts per year, using a staff of just 70, many of whom came to the shop with no machining experience.

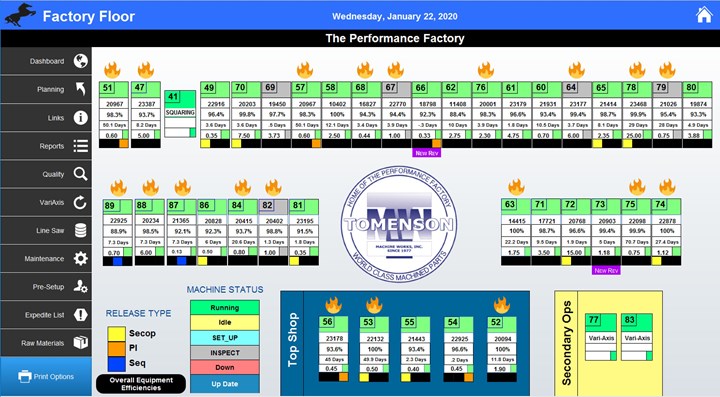

Given the large volume for the level of staffing, you might expect Tomenson’s story to be about automation. It is about something else instead. This shop has set itself up for efficiency and continuous improvement by standardizing in three major ways: 1) specializing in precision hydraulic manifolds, 2) buying nothing but similar models of Mazak HMCs and 3) developing and integrating custom software used on iPads to unite the work of every employee and department in the business.

Mazaks as Far as the Eye Can See

Let’s take a walk. Upon entering Tomenson Machine Works, you’ll find yourself in a newly renovated atrium area. The rest of the facility wraps around this centralized common place in a giant, upside-down U divided into eight units. All the units have glass windows and easy access to the atrium area. When Tomenson first moved to the building, these different units housed other businesses, but Tomenson has acquired each unit over time, one by one, so that it now owns the entire building — a building practically perfect for standardized workflow. Now, to walk through the 8 units in the “U” is to walk through Tomenson’s process. The first door from the right of the atrium is Unit 1 — raw material incoming. All work eventually flows up, left and back down the U until it reaches Unit 8 — shipping.

Tomenson’s standardization efforts are obvious beginning in Unit 1. The company uses just one supplier for incoming blocks of aluminum, steel and iron. In the past, the shop would cut the blocks itself, a seeming cost savings that in fact added complexity to the process. Now, the company orders its materials in standard, pre-cut sizes that are ready for machining.

At the top of the U are Units 4 and 5, the “Performance Factory.” This is where the main manifold machining takes place. Either side of the central walkway is flanked by nothing but Mazak HMCs. And any walk through the shop’s process simply has to stop here to consider (maybe even marvel at) the impressive similarity and vast number of machines in this section of the building — 40 total, running 24/7.

To the extent that it is able, Tomenson has been buying the same make and model of Mazak HMCs since the early 1980s, when the shop purchased its first CNC machining center. Mazak has advanced and improved its machines since then, but this is the only reason for differences among the machines in this bay. For decades, Alex says the company has taken the “Southwest Airlines approach,” referring to the airline that famously purchases only one model of plane. Some shops remain true to one machine tool builder, but Tomenson has also remained true to one HMC model.

Continuous Improvement Through Standardization

It was decades ago, during the time of the shop’s transition from manual machines to CNC, that Tomenson decided to standardize on its product offerings, focusing almost solely on machining hydraulic manifolds. The orders for these parts — a mix of high and low volumes — changed the company’s trajectory because of the way many of these jobs run for months, if not years.

Because of the manifold focus, almost all of the machining done at Tomenson is holemaking, and almost all of these holes are oriented in right-angle directions, which is perfect work for the HMCs with just X, Y and Z axes and a pivoting B axis. When a manifold requires a hole to be machined at a compound angle, that work is done in a secondary operation on a five-axis machine. Machining cycles for manifolds can run for two hours or more, as the shop runs the parts in batches. Because of this, setup on any one machine doesn’t need to happen very frequently, but each machine could still see 5-10 setups per week.

In the past, setup used to be a process in which the operators pulled their own tools and built their own fixturing. However, standardizing on manifolds has let Tomenson develop a highly efficient process in which employees coordinate to proceed quickly through four well-defined steps: 1) fixturing, 2) tooling, 3) pre-setup (removing previous jobs’ fixturing and tools) and 4) running the first piece. Moreover, the manifold work has enabled Tomenson to develop custom fixturing and tooling that the company is able to standardize to a high degree. The four-step setup system has become so efficient that Alex questions certain types of automation. “Adding more complexity to a process doesn’t always make it more efficient,” he says. “Sometimes, it actually makes it less so.”

The shop has implemented a variety of visual cues to make sure that work ends up in the right place. For example, looking around the shop floor, anything stacked on a skid with yellow cardboard is going to get an angled hole in secondary machining, anything stacked on a skid with brown cardboard will go to deburring and each machine displaying a green sign indicates the job has gotten first-piece inspection.

A Skills Gap Solution

Standardizing on one HMC model is also valuable for the way it streamlines Tomenson’s training system. Often, Alex says, the company has to hire employees with no experience running CNC machines. That being the case, all employees in this section of the shop are hired in as operators. After gaining experience, they can advance their training and work their way up to a setup position, which is a desirable title in the company because it requires problem solving and provides a variety of work. Having only one machine to learn sets new employees up for success, and it makes it easier for operators (and programs) to be interchangeable. “Our operators know all the machines, and this way, they know all the simple fixes,” Alex says. This has also given the shop the ability to have only one dedicated maintenance person on staff.

Efficiencies such as this have allowed the company to now run much leaner than it did before the Great Recession. Each operator is responsible for multiple machines, and the operator’s main function is to keep the machines running. Over time, the shop has been able to expand how many machines each person is able to oversee effectively. According to Alex, Tomenson employed more than 200 people in 2012. Today, thanks to improvements such as this, he says the company employs about 70, but they are twice as efficient as they would have been in the past.

The Glue That Holds It All Together

The final level of the company’s sophisticated standardization hinges on the company’s custom software, “FilePro,” which Scott developed over a 10-year period. During this time, he saw how necessary it was to have a central hub that could effectively communicate necessary information around the entire business. Setup, operator, inspection, deburring and shipping employees all have access to the software using their own portals, which can be accessed on any of the 60 Apple iPads located on the shop floor. Employees simply log in with their employee number and record their production information.

According to Alex, Tomenson uses FilePro for every job shop information input the company has been able to recognize. “The iPad system is truly unique,” he says, referring to the unusual step the shop took of developing a shop management system on Apple’s platform. “Even the timeclock is done through it. We track so much data. We can tell when parts will go bad before it happens. We put it in a graph, and we can see if the tolerances are getting out of range.”

If a machine goes down, the operator can take a picture and write a description of the problem. This alerts the setup employees via email to hurry to the machine and get it running as soon as possible, Alex says. FilePro is also used to store information for the company’s custom, standardized tooling. Tool data, tool lists, fixturing instructions and scheduling information can be accessed by pre setup personnel, and then setup personnel can be emailed when the machine is ready for them. This central information hub also ensures that the machines are always running the most recent CNC program.

Another benefit of the iPad system is that it’s part of the company’s training strategy. “Since we’ve given new employees all the info, they’ve been almost self-training on inspection. Plus, if they are recording an inspection that is out of tolerance, they don’t need to know what to do to address it — a ticket will be made automatically explaining the situation,” Alex says.

And this is just the information that is used around the Performance Factory. FilePro is used elsewhere, too. Let’s keep moving — we’re not yet done with our walking tour.

Post Production

Behind the setup room is the inspection room. Due to the critical role manifolds play in million-dollar machinery, Tomenson has always machined its manifolds to high standards. But two years ago, one of its customers began requiring 400-micron tolerances on particulate left in the part. To meet this requirement, the company has engineered an aggressive wash station that all manifolds now go through multiple times.

Unit 6 is deburring. Also in response to the tightening particulate requirements, Tomenson decided to start using a thermal deburring process to complement some of the manual deburring of its manifolds, a shift that reduced staffing by 20-30 people. Tomenson has recently taken delivery on an Extrude Hone system for thermal deburring, which comes immediately after the washing step.

From deburring, the manifolds move into Unit 7 for packing and Unit 8 for shipping. In packaging, the FilePro software plays another crucial role. It gives employees visual cues by showing photos of exactly how the parts should be packaged to be shipped. “It’s an important part of the process that would be easy to overlook,” Alex says. For example, if someone accidentally mislabeled a package or put the wrong item in a package that is shipped, it’s the same thing as shipping a non-conforming part in terms of defective parts per million (dppm), he says. “You could do everything right through the entire machining and post-production process, but if the wrong item is sent to the customers, it would be a huge, costly fail for our company.” Barcode scanning is built into the FilePro software so parts can be traced, and this ID now helps ensure that every part is packaged as it should be. The software has information on how long it should take to package the part and photos of how to do so, Alex says.

Tomenson’s fine-tuned standardization didn’t happen overnight. The family members and the employees have advanced in gradual steps to make the process of machining manifolds as easy and as efficient as possible. And this process hasn’t stopped. According to Alex, employees are constantly typing suggestions into the iPad system — continuous improvement is built into the company culture. “We take all suggestions seriously and improve things as the job runs,” Alex says. “Some jobs we’ve been running since the ‘90s, and we’re still improving on their processes.”