This article by Brent Donaldson originally appeared in Modern Machine Shop magazine.

Without a natural successor for his business, Geno DeVandry faced the real possibility that he would be the last in his family to run Deking Screw Products, a machine shop started by his father outside of Burbank, California in 1962. Geno had been running the shop on his own since he was 19 years old in the mid-1970s. In 2015, 40 years later, he still relied on the half-dozen Acme brand multi-spindle screw machines that the shop used for production since it first opened.

When the Great Recession hit in 2008, Geno DeVandry had to let go of 40 of Deking’s 43 employees, some of whom had been with the company for decades. The Acme screw machines largely sat idle in the following years, with each passing week presenting a new slate of worries. “There were times when I thought, man, I’m not going to make it,” he recalls.

It was a conversation in late 2014 with a family friend about Swiss-type machining that began to turn things around. DeVandry was a girls’ youth-league soccer coach who often chatted after games with his players’ parents, including a man who happened to be one of the top Swiss-type machining experts on the West Coast. DeVandry remembers the day that Jouni Levanen, then an applications engineer for Marubeni Citizen-Cincom, visited Deking to see a complex part that DeVandry had recently machined.

“I came to visit Geno and he was holding up a really intricate titanium part that he made in six operations,” Levanen says. “And I said, ‘I can make that on the Swiss, done-in-one.’ He didn’t believe me. So, I did a time study and told him it would take 90 seconds to make the part.”

So impressed by what Jouni had told him about these machines, Geno and Jouni decided to team up in what would essentially be Deking Screw Products 2.0 — a precision parts manufacturer that offered CNC Swiss-type machining.

With the agreement in place, Geno abruptly canceled an order he had just placed for a new wire EDM machine — a machine Geno intended to make tooling for Deking’s Acme machines — and ordered Deking’s first Citizen-Cincom A20 Swiss-type machine instead.

Fast forward to today, and the company now owns 10 CNC Swiss-type machines. The introduction of this kind of machining at Deking Screw Products did more than offer a new and highly efficient production method to the business. It also convinced not only Jouni Levanen to join the company, but also Geno’s youngest son, David, who had studied engineering in college but switched his focus to work for an education startup company.

Since no one at Deking besides Levanen was experienced with programming and operating Swiss-type machines, it meant that Levanen, who today runs the business alongside David DeVandry, had a lot to teach to his new colleagues.

I recently talked to the DeVandrys about the ownership succession of Deking Screw Products from Geno to David — a conversation you can listen to on the “Made in the USA” podcast, or read about here. But I also asked Jouni Levanen about some of the nuances of Swiss-type machining that he has been teaching to the uninitiated at Deking — and about what makes these complex machines a superior method for producing the small, intricate aerospace and medical parts that the company primarily manufactures today. These nuances are technical, of course, but they also require a mindset change and a reprogramming of how even experienced machinists think about CNC machining.

The First Swiss Arrives

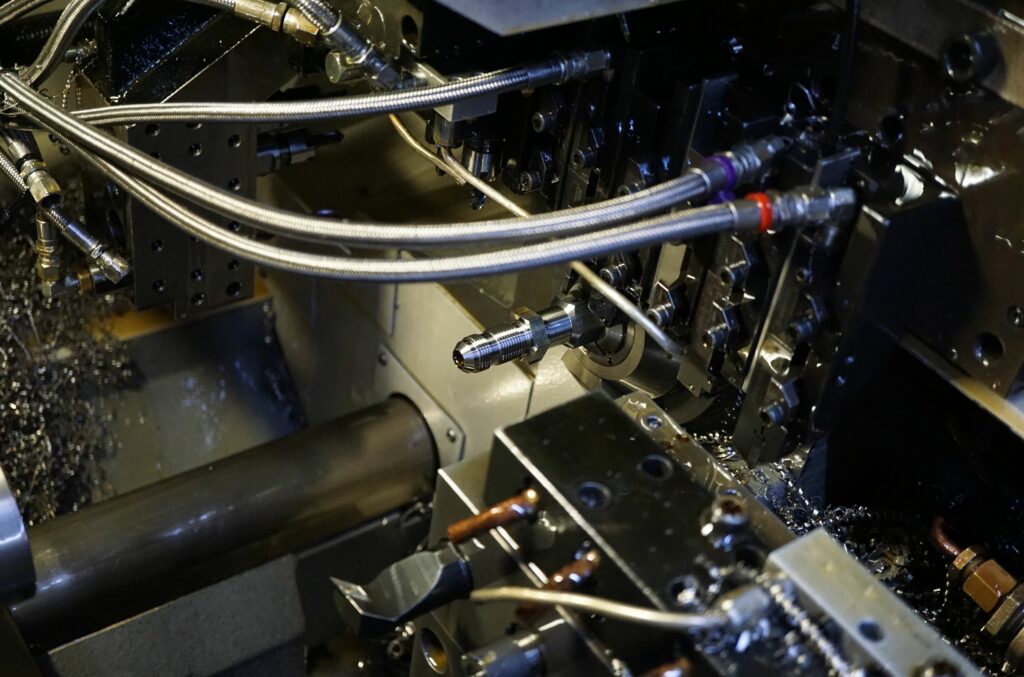

When the first Cincom A20 arrived in 2015, Levanen and Geno DeVandry set it up and ran test cuts through the night. The next day, the decision was made to begin shifting production to the A20 for certain parts, mainly fasteners and fittings, that Deking had been manufacturing through multiple operations on the Acmes or traditional CNC lathes. Machining a threaded fastener with a slot on these machines used to involve hand-chamfering, tumbling operations, and then separate setups for slotting and thread milling. But with the A20’s five axes, four rotary tools and subspindle, and an X2 axis on the back spindle that allows for simultaneous front-and-back machining, Deking routinely produces these parts in one operation.

Time savings leading to increased throughput from producing parts in one operation is clearly the most immediate benefit of the Swiss-type machines — not only because of their “done in one” capabilities, but also because of technologies like direct C-axis indexing, which saves time by the capability of the spindle to decelerate to any chosen index position, thus eliminating the need to perform a zero return with each pass.

But a corollary benefit that the DeVandrys noticed immediately was increased cutting tool life. Swiss-type machines use a sliding headstock that moves along the Z-axis while feeding a rotating bar stock through a guide bushing. Since the headstock can slide behind the chuck, it allows X-axis cutting to take place close to the guide bushing. Not only does this enable the machining of long, thin parts, but the proximity between the cutter and the guide bushing drastically reduces deflection from cutting forces on the workpiece. Naturally, this extends the life of cutting tools.

Another reason for extended tool life? Most if not all Swiss-type machines use oil instead of coolant, which not only allows for better chip control, but also lubricates the guide bushing, bearings and cutting tools. “Tool life goes through the roof,” Levanen says. While cutting oils are not as effective as water-based coolants for temperature control — a fact that necessitates fire-suppression systems and the availability of gloves to handle tool changes — the cutting oil uniformly absorbs heat away from the cutting surface, which helps Swiss-types machines routinely achieve tolerances of ±0.0002 inch (sometimes even less) by reducing thermal expansion of the workpiece.

He Makes it Sound Easy

In addition to the six Citizen-Cincom A20s, Deking Screw Products also owns two Cincom L12s and two Cincom A32VIIs, with bar capacities that range from 0.5 to 1.25 inches. Today, more than 80% of Deking’s production happens on these machines, and that percentage is growing. As the company has grown, so has its profit, as well as its ability to rehire several of the machinists that were let go after the last recession. To get to that point, for everyone besides Jouni, the introduction of Swiss machining at Deking required a mindset change for its employees. The complexities of these machines present process control challenges that may seem counterintuitive to operators of other types of machine tools.

Jouni explains. Relative to other types of CNC equipment, the first (and according to him, the easiest) difference to understand relates to programming. A traditional CNC lathe’s turning tool feeds in both X and Z to engage with a part, and the face of the bar stock is considered Z zero. In a Swiss, the offset is reversed. It is the headstock that moves in the Z direction so the bar stock feeds into the cutting tool in Z. So, Z zero is still in the same place, but the moves associated with positive and negative are reversed.

“Once you remember that anything that you want to make bigger [that is, longer part, deeper hole], you go plus, and anything you want to make smaller, you go minus — once you get that through your noggin, it’s really just the same thing as typical CNC programming,” Jouni says. “You also have radiuses, and radius clockwise is a G2 (circular interpolation code), and radius counterclockwise is a G3. So now, when you switch from going minus, your Z axis is traveling in a different direction. Other than that, it’s the same thing.”

“He makes it sound a lot easier than it is,” adds David. (It should be noted that Jouni Levanen programs by hand and prefers not to use software. But that’s another story.)

Another critical difference in CNC programming and machining with Swiss-types is more tactical in nature. Because Swiss machines are typically used to produce parts with length-to-diameter ratios that require guide bushing support, workpieces are machined in segments.

This is necessary in order to keep the section of the workpiece being machined fully supported by the guide bushing. Rather than roughing then finishing the entire part, part segments are machined in full using as many spindles and tool changes as necessary before moving on to the next segment. This includes ID and OD threading, which remain seamless despite this segmentation.

“When you start with the Swiss-type screw machines, you always want to do any ID work first,” Levanen advises. “Then you can start doing the segment turning for shoulders and grooves, and then continue with the rest of the part.” These segments typically measure 0.750 inch in length to maintain the rigidity provided by guide bushing support.

Underscoring this is the importance of raw material quality, which Levanen says has improved drastically over the last 20 years. Deking requires its material providers to supply bar stock that maintains ±0.001 inch in diameter across the length, no matter if the material is aluminum, stainless or alloy steel, titanium, plastics, high-nickel alloys or tool steel — all of which the company machines. Deking no longer grinds its bars to achieve these tight tolerances, or the required straightness, which should be less than 0.001 inch per foot. Levanen typically prefers carbide-lined guide bushing because of their high rigidity and resistance to wear.

Combined, all of these changes have allowed Deking Screw Products to become a steady aerospace supplier, achieving AS9100 certification, as well as a grow its reach into the medical, defense, electronics and commercial industries. The shop also runs parts on traditional CNC lathes and uses its own EDM machine to produce tooling for them. But the nature of its work and its customer base is changing because of what Swiss-type machining brings to the table.

At this point in our interview, Geno DeVandry, who still occasionally works at the shop, chimes in from the back of the room. As you can hear for yourself, it was not easy for him to see the nature of Deking’s business change so drastically in such a short period of time. But it’s clear that he is thrilled with the success that Jouni and David have built upon his leadership for the past 45 years.

“The really important thing about this kind of business is that you have to keep trying new things, because things are changing constantly, faster and faster,” he says. “And even when I was running this place, one of the strengths that we had was that we were willing to try new things all the time. And that’s continuing now, because things like carbide coatings for the bushings he’s talking about — the materials are changing. Tooling is changing every day. You have to always keep trying new things.”