This article by Matt Danford originally appeared on the Modern Machine Shop website.

Continuous improvement comes naturally for experienced machinists, but instinct goes only so far without formally monitoring and documenting the effort.

A case in point is Levy’s Machine Works, a 40-year-old, 10,000-square-foot CNC machine shop in Western Canada. Tasked with implementing a formal continuous improvement program after a 2014 acquisition, the team was skeptical at first. There seemed to be no way to administer the program without cutting into capacity for quality customer service and on-time delivery.

However, the team had wide leeway to implement the new system in a way that made sense for Levy’s, says Richard Burton, general manager. Once adapted to the realities of a high mix of low-volume machining work, the more formal approach proved its worth. “Capturing, documenting and tracking improvement ideas and efforts is often seen as a challenge with no tangible benefits, but not doing this means improvement opportunities are also being left to chance in terms of being missed or captured and actioned,” he says.

The caliber of the talent at Levy’s essentially provided a head start.

So far, the work associated with continuous improvement has boosted revenue by 15 to 20 percent and reduced overall operational losses by nearly 11 percent. Leaders at both Levy’s and the parent company attribute these gains to improved resource management, machining capacity and planning and scheduling.

Other benefits are less tangible, but no less important. As opposed to busywork – a series of rote tasks to be completed unthinkingly and without question – the data entry and other tasks required to comply with a formal platform have made it more likely for employees to suggest and actively pursue positive change. “(The program) has boosted the culture of continuous improvement we already had,” Mr. Burton says. “While it has added a few more minor tasks, it has also engaged people more with the business.”

Flexing Theory Into Practice

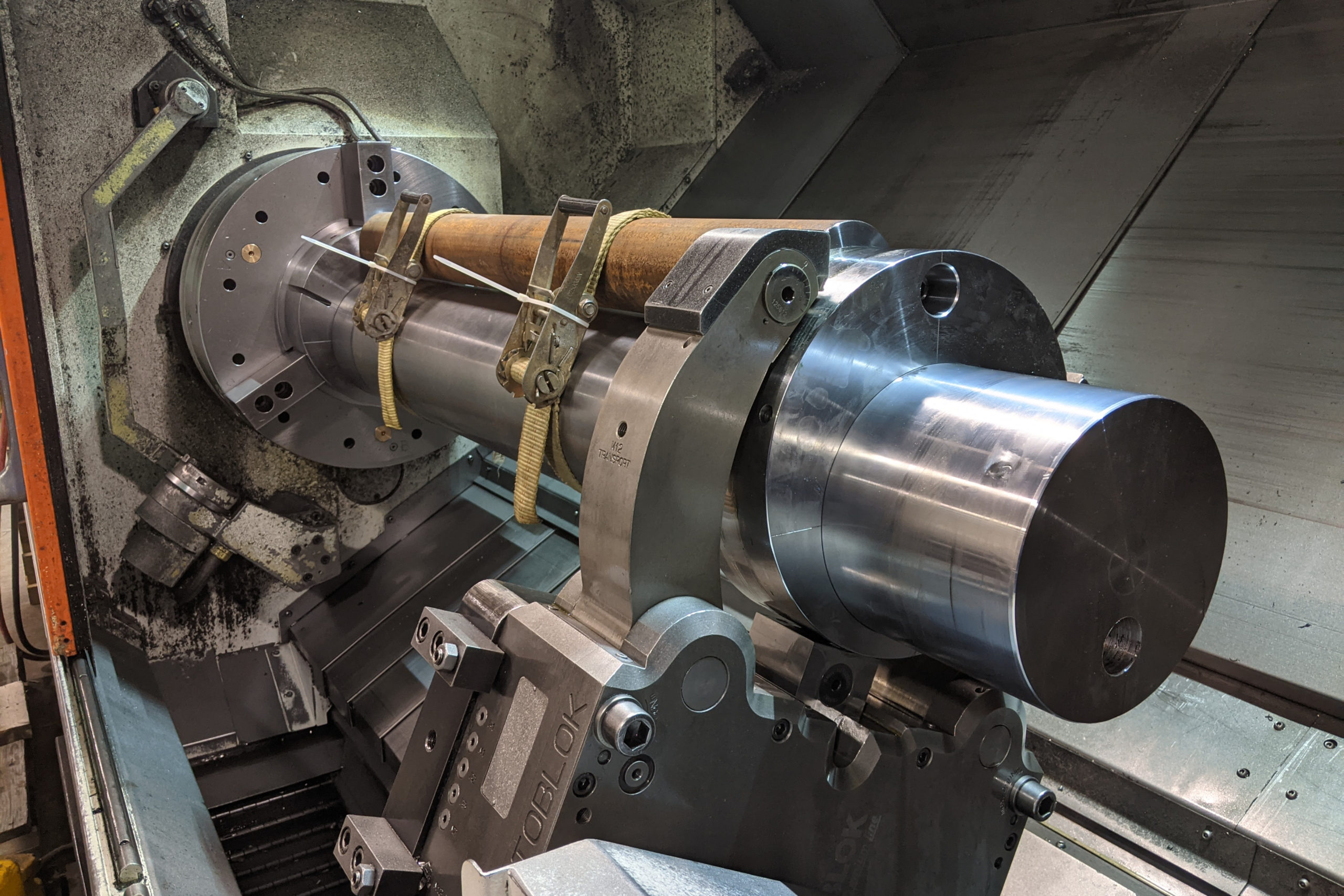

The caliber of the talent at Levy’s essentially provided a head start for continuous improvement when Mr. Burton joined the company in 2015, shortly after the company’s acquisition by investment firm Equicapita. “We achieved ISO in five months,” Mr. Burton says about his crew, who specialize in turning and milling complex geometry from such difficult materials as austenitic stainless steel and beryllium copper. “The people here can take a job from blueprint to the finished article, and so they are used to coming up with the best methodology, program and set-up. It’s in their nature to continuously evaluate their tools, practices and the environment they are working in, and to make any changes they feel would be of benefit.”

Still, the task ahead seemed daunting. Compliance would require weekly and monthly scored audits as well as extensive documentation of material losses and defects, overruns, (estimated versus actual machining and/or setup times); and total numbers of waste walks, gemba walks, 5S audits and Kaizen projects conducted. It demanded that various checklists, prioritization and effort matrices, and the use of 25 different lean tools become part of the daily routines of people that, as Mr. Burton puts it, “already have busy day jobs.”

“Ultimately, there are 72 things that need to be implemented, tracked, audited and reported on in various meetings,” he continues. “It looked like it would be impossible to cover without a department or team to implement and administer it.”

Mr. Burton characterizes the formalization of continuous improvement as a unique selling proposition.

Nonetheless, he saw the promise in a system that combines elements of lean manufacturing, six sigma and total production maintenance theories. He also received assurances that the program was not one-size-fits-all, despite its application across Equicapita’s diverse 12-company group. For instance, machine utilization and OEE reveal less about Levy’s performance compared to another manufacturing group member where repeat, high-volume work is common. In contrast to that company, Levy’s might have anywhere from 400 to 700 different parts on order at any one time. Each might take any number of different routes through the shop, and setups are lengthy. Given these and other realities, comparisons of estimated to actual production and setup times are better performance indicators.

On a more granular level, easing implementation would require consolidating goals and tasks and integrating new tools. It also would require getting the team on board with the value of a formalized approach, both for the business as a whole and their own careers.

The Tools of Improvement

Among other practical changes making implementation possible, Gemba and safety and 5S audit walks have been combined, and are less frequent. Various forms and spreadsheets have also been consolidated and simplified. Perhaps the most notable example is the Kaizen Suggest/Job-time Overrun form, which, as the name implies, captures information required for multiple continuous improvement program reports. Management reviews the forms weekly and documents the potential improvements in a Kaizen project prioritization spreadsheet.

This form must be completed whenever a job operation overrun exceeds a certain threshold (say, 30 percent). It contains fields for job number; part number; step number; setup or cycle; estimated (setup or cycle) time; actual (setup or cycle) time; the reason for the overrun (tooling, program, first-time run, quality control, workholding, or “other”); specific issues or problems to be resolved; and, finally, ideas for Kaizen projects to improve the process. These ideas might be suggestions for improvement on a single process, or it could be something that affects the whole business. “We capture everything we need on one form,” Mr. Burton says.

This form must be completed whenever a job operation overrun exceeds a certain threshold (say, 30 percent). It contains fields for job number; part number; step number; setup or cycle; estimated (setup or cycle) time; actual (setup or cycle) time; the reason for the overrun (tooling, program, first-time run, quality control, workholding, or “other”); specific issues or problems to be resolved; and, finally, ideas for Kaizen projects to improve the process. These ideas might be suggestions for improvement on a single process, or it could be something that affects the whole business. “We capture everything we need on one form,” Mr. Burton says.

The tools of improvement consist of more than just cleverly consolidated forms and reports. Domo, a data visualization software tool, integrates data from EquiOne-related forms and reports as well as other software into at-a-glance dashboard displays that provide a “clear window into all aspects of the business,” Mr. Burton says. That view from that window is always in real time because employees on the shop floor use tablets to indicate the start and finish of every operation on every part they touch. Transmitting this information directly to the shop’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) system (Shoptech Software’s E2) — and to Domo from there — ensures that every operation time and overrun is documented.

The tools of improvement consist of more than just cleverly consolidated forms and reports. Domo, a data visualization software tool, integrates data from EquiOne-related forms and reports as well as other software into at-a-glance dashboard displays that provide a “clear window into all aspects of the business,” Mr. Burton says. That view from that window is always in real time because employees on the shop floor use tablets to indicate the start and finish of every operation on every part they touch. Transmitting this information directly to the shop’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) system (Shoptech Software’s E2) — and to Domo from there — ensures that every operation time and overrun is documented.

On the shop floor, clear views of queued work help employees prepare programs and tooling in advance. By the time this article is published, digitalizing hard copies of setup sheets, drawings and other such documents likely will have further reduced the amount of paper in the shop, but much of the benefit of the new approach is already apparent. Employee utilization (paid time versus productive time) and production efficiency (estimated versus actual operation times) can be properly tracked. “We previously relied on winning more than we lost in terms of making margin on work. Now we can look at how we’re doing while we’re doing it for every operation and every job, and we can take the required action to improve,” Mr. Burton says. “When it comes to reporting up at the end of the month, we know exactly why our profit margins were up or down, which jobs and operations were the issue, and why.”

All Aboard

Practical changes and new tools aside, making continuous improvement work would require winning the hearts and minds of the people who program, set up and run the machine tools. One means of accomplishing this is to have members of the team directly participate in managing the effort by formally auditing one another for compliance on a bi-weekly basis. “We’ll pick somebody – maybe it’s a machinist, or maybe someone in shipping/receiving or office administration – and for 40 minutes, that is the most important person in the building,” Mr. Burton says about the rotating auditor, who walks about the shop with checklists of items to evaluate.

Covering every department and consolidated from a more in-depth annual audit, these checklists are worded so that essentially anyone can audit anyone. Audits are random, and they encompass every employee in the company. In addition to ensuring compliance with continuous improvement program and quality management system standards, employee auditors are exposed to the role of how other job functions and skills (including their own) fit into the broader organization. The audits also foster a sense of friendly competition that benefits efforts to improve (Mr. Burton notes that employees often seem particularly eager to find improvement opportunities at the workstation of the previous auditor).

Leadership also has taken steps to ensure that employees’ voices are heard, and that they understand the link between formal performance tracking and recognizing and rewarding their work. One example is a system in which the shop pays half the cost of a machinist’s personally owned measuring tools if the machinist can prove that the investment would be worthwhile. “If they can justify that they use it frequently enough, we’ll benefit as a business by picking that up,” Mr. Burton says. “It’ll show up in avoiding issues with nonconformance through damaged tools or using the wrong tool for the job.”

An “open-door” culture is also critical, he says. “We want people to question things they aren’t comfortable with and be able to make their thoughts and ideas known,” Mr. Burton says. “We want them to feel like they’re part of something bigger than just a job, where they’re told what to do.”

Word Spreads

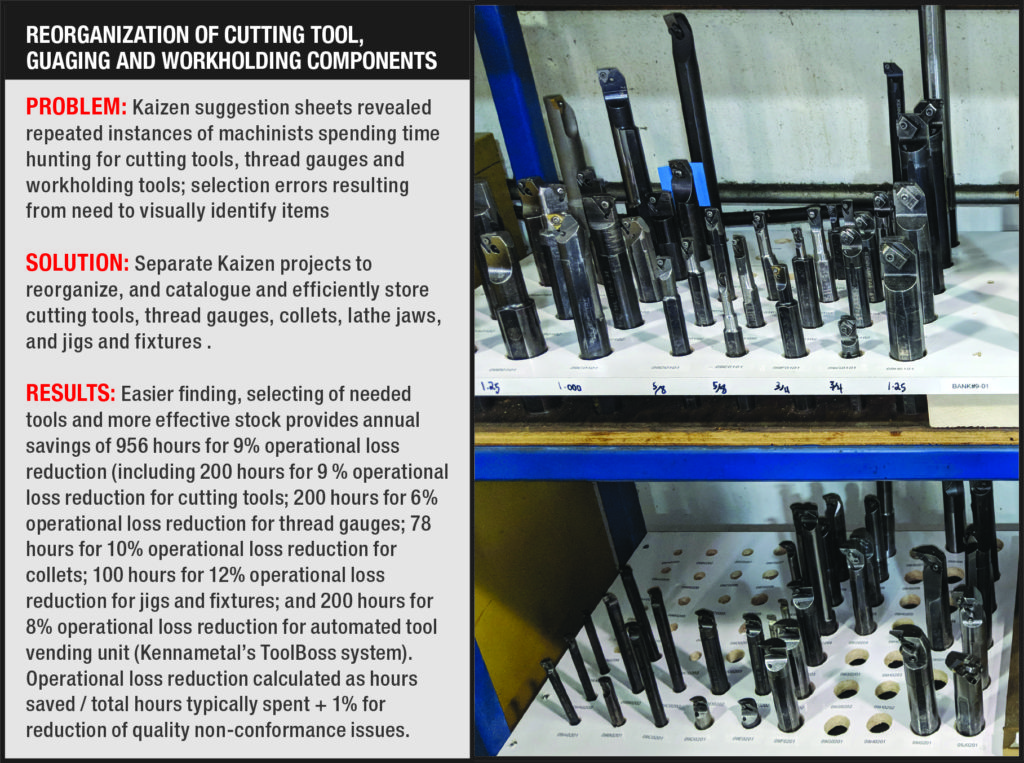

Each of the images in this article details a specific Kaizen project. Altogether, these examples represent only a portion of the most significant results of continuous improvement. In fact, benefits of Levy’s particular implementation of the parent company’s platform extend beyond the shop. One aspect of Levy’s approach, regularly and formally recognizing the people behind the top four most impactful, recently completed Kaizen projects, has since been adopted at other companies.

The shop also ensures customers and prospective customers are aware of internally focused improvement efforts that go beyond what is necessary to meet ISO quality requirements. In fact, Mr. Burton characterizes the formalization of continuous improvement as a unique selling proposition when approaching prospective new customers. “We have something tangible to show them by way of project summary sheets and reporting and tracking,” he says. “Many are surprised that a business the size of Levy’s actually focuses time and resource in this area. It helps to set us apart from other shops.”